Ramzi El Saidi: Lifetime of Art collecting sums up a lifelong love

SPNL.ORG is republishing this article in memory of SPNL late president Mr. Ramzi El Saidi who died on Wednesday 28th of March 2018.

It is said by artists and critics alike that the most important collections of art in the world are amassed not by museum committees or panels of jurors but by individuals. And moreover, that such collections tell you as much about the collector as the works of art collected.

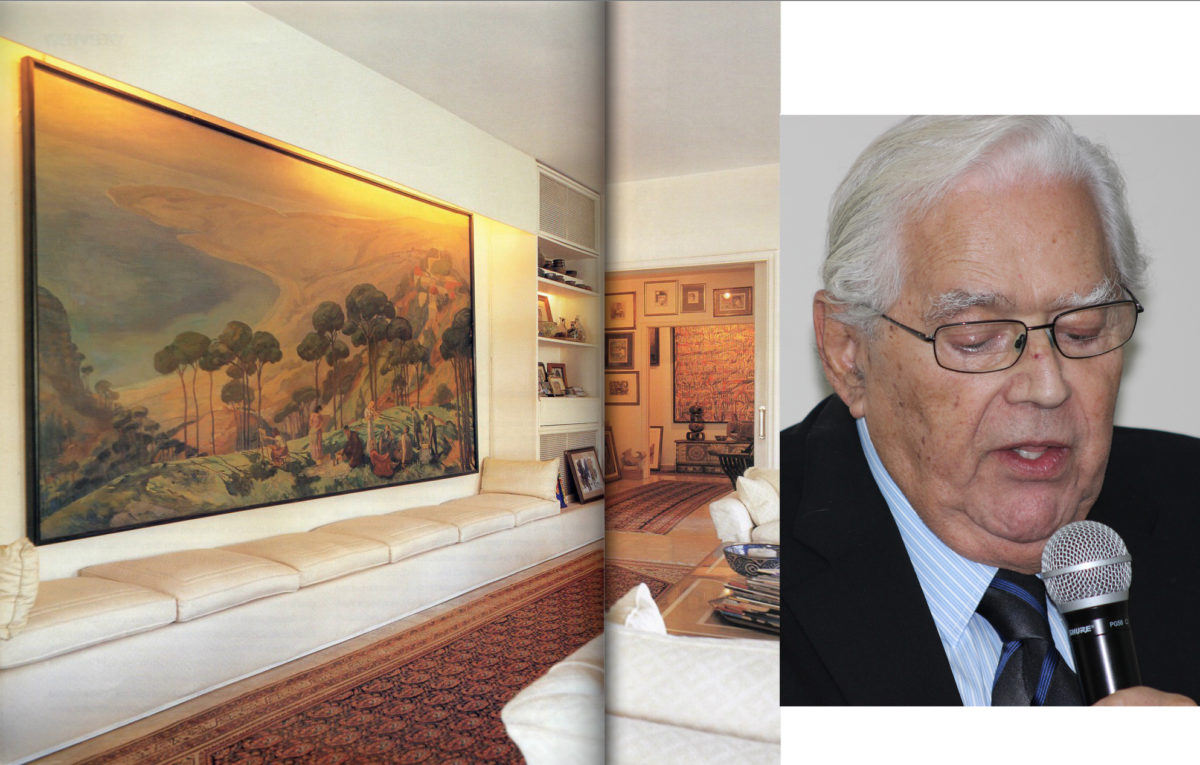

This is certainly the case when it comes to Ramzi Saidi, the owner of what is acknowledged in the local art world as probably the country’s largest private collection of Lebanese art.

Like the paintings and sculptures populating his Ramlet al-Baida home, Saidi is a man of strong opinions, full of color and passion. Like him, his collection is unique.

According to art critic Samir Sayegh, it is unique because it is one man’s view of what he likes, not motivated by theme or vogue or money, but by a simple love of art and his country.

“What I know without any doubt is what I like and what I like is what I can live with, what I can sleep with. This is the most important thing about the motivation behind my collection,” Saidi says. “No one has any control over my buying. All the art in this house is reflective of my personal experiences since childhood.”

Walking around his home Saidi points out various artists and sculptors like the 1940s romantic impressionists Omar Onsi and Mustapha Farroukh and the famous early 20th century pioneers like Daoud Corum and Habib Srour. The incredibly varied collection is clearly representative of Lebanon’s artistic talent and heritage.

“I began collecting in the late 70s, during the war, when very few people were collecting art. It was especially after the Israeli invasion of 1982 that I bought a lot. It was a time when I was worried about the future of the country, and when I seriously believed we should be doing something to preserve as much of our artistic and cultural heritage as possible,” Saidi says.

He currently has over 600 works encompassing 60 Lebanese artists but says the number was at 700 during the war.

“In those days it was an obsession, a passion. I was in a state of mind to acquire. Now I am less emotional about collecting, and more objective. I try to buy more younger artists these days when possible.”

Saidi says his collection is more comprehensive than others he knows of, not only because of the quantity but because of the range of artists, not necessarily all famous or fashionable, and the amount of different artistic mediums used.

“The collection represents all the different aspects of the Lebanese art movement since the beginning of the early 20th century,” he says.

The medium is clearly important as it shows the versatility of art practiced in Lebanon.

“I have almost every medium here oil paintings, water colors, gouaches, drawings and sketches, sculpture, ceramics and pottery, prints including engravings, lithographs, monotypes and etchings and other works in mixed media such as collages, cut outs and acrylic,” Saidi explains.

“But the most wonderful thing about the collection is that it is a living collection. It is constantly changing within the space we have. And we like people to come to enjoy it with us participate in the art. It is an interactive process,” he says.

Not content to keep his collection at home, Saidi has lent many works to galleries and museums, from the Sursock and the Lebanese American University in Beirut, to various galleries in Paris and London.

“Despite the fact that during the war it was both costly and very dangerous to handle and move the art, both my wife and I believed this was integral to keeping the collection as interactive as possible.”

He relates a story of how his house was close to the State Security offices and thus in the line of shelling during Michel Aoun’s 1989 rebellion, prompting his wife and children to fill sandbags, placing them on the outside walls of rooms containing paintings. “We used to count how many walls the shells would have to pass through before they reached the paintings.”

It is lucky that very little was damaged.

As a result of his and others’ efforts, Lebanese art has become known to an international audience. Last year, Sotheby’s held its first sale of Arab and Lebanese art in London. Works by the Lebanese romantics and by the early classicists like Khalil Saleeby and Morani, as well as the modern Lebanese artists such as Chafic Aboud and Paul Guiragossian, sold well above their asking prices.

“They fetched higher prices than they could in Lebanon due to the depressed economic period we are in at the moment,” Saidi adds.

He explains that he has never bought art as an investment. The market is not big in Lebanon. Only about 4 or 5 percent of the population buy art. “The people who invest in art here are few. There are just a handful of dealers. Many big collectors are progressive banks like Banque Audi and Bank Mediterranee.”

Fortunately for those who have bought art as an asset, most have made good on their investments, although prices have been stagnant in recent years due to the recession. Important artists of the 1940s and 1950s like Onsi and Farroukh sold then for a few hundred dollars and are now worth several thousand dollars. Unique works sell for much better prices.

“But as art follows fashion, certain artists popular 20 or 30 years ago are not popular today and are difficult to sell,” Saidi says. “I personally bought many works of art in the mid-80s that have not increased in value at all in today’s depressed market.”

Saidi also serves as director of SARI Lebanon, a technical documentation and translation company. He is president of the environmental charity Society for the Protection of Nature in Lebanon and vice-mayor of the southern town of Jwayya. He is also on the steering committee responsible for setting up a new arts center at AUB.

Source: Ramsay Short, The Daily Star, Jan. 07, 2002