Fighting Land and Ecosystem Degradation in Lebanon

As a general methodology and for each sector or issue tackled, Support to Reforms – Environmental Governance (StREG) Programme carried out initial analysis, developed as necessary good practice guidelines, road maps, protocols or recommendations, and translated the latter into legislation. Protected Areas Lebanon boasts 15 protected areas covering 3% of the Lebanese territories. They are the main conservation tool in a country exposed to fierce competition over resources. Protected areas are an attempt to protect precious natural resources, vegetation cover, and wilderness from a wide array of threats most important of which is urban encroachment.

According to the SoER, urbanization is the main driver of habitat loss followed immediately by forest fires, agricultural expansion, overgrazing, quarrying, climate change, and conflict. With mounting economic pressure, aggravated by the explosive refugee situation and dwindling oil prices in the region, urbanization, and growth of cities and villages reflect the global trend where people are instinctively drawn to successful and attractive natural sites. These dangers present themselves in a context marred by lack of data on land use, land cover and land tenure as well as very poor master planning. More than 50% of the country is still not surveyed and boundaries are not demarcated including in Protected Areas. This situation is juxtaposed to the fact that in Lebanon, private property is sacred. This sanctity of the private is anchored in the country’s constitution. The highest level of the law stipulates that no land can be taken away from its owner except in cases as established by law and only after the owner has been duly and fairly compensated. In other words, landowners have a free hand to develop property even if this affects fragile and valuable ecosystems. According to the SoER, this situation has so far impeded sustainable land use planning, conservation and the delineation of protected areas. StREG targeted one of the most important Protected Area contexts to treat this situation and set precedent and groundwork to build on and replicate in other regions.

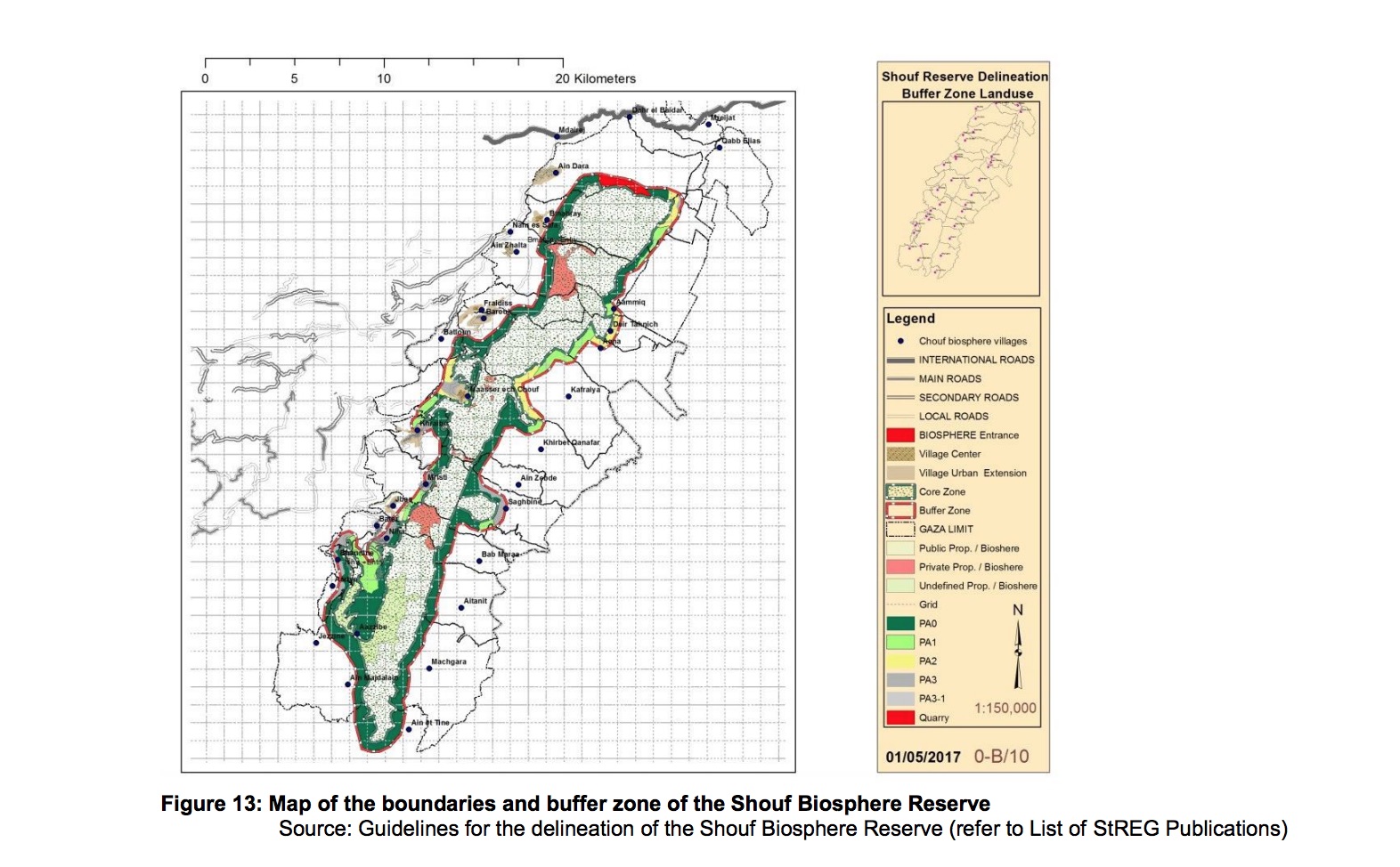

The Shouf Cedar Biosphere Reserve (SBR), a mountainous range of forest land surrounded by 26 villages, is the largest protected area in Lebanon. Yet despite good relations with the surrounding local communities, the management team of SBR constantly deals with challenges and threats related to development and encroachment. With the support of StREG, the SBR was delineated, demarcating the core area and the buffer zone while identifying private, municipal and communal lands. StREG organised the buffer area using a zoning system that divides it into four categories of different levels of use and tailored to conservation needs (refer to List of StREG Publications). The integrated conservation concept allows for green development in the buffer zone of the protected area, detailing specific construction systems and certain specifications to minimise adverse impact.

“Delineation is the basis of effective management of protected areas. Without clear boundaries and an organised buffer zone, we cannot practice conservation and engage local communities.” – Nizar Hani, Department of Ecosystems, MoE; and Shouf Cedar Biosphere Reserve Manager

StREG also developed a methodology for delineating protected areas to allow replication of this important practice in other sites. StREG also addressed a recurring procedural aspect in the buffer zones of protected areas and, which concerns well’s drilling. For this purpose, StREG brought on board specialist consultants to develop detailed and scientifically based guidelines for effective management of the wells in the buffer zones of protected areas (refer to List of StREG Publications). 30 Through the delineation work and other support, StREG has yielded a positive influence on the governance of Protected Areas in Lebanon as a whole. Quarries The quarry sector is one of the thorniest sectors in Lebanon. The sector is vastly chaotic and unregulated with almost complete absence of law enforcement. Disorganization in planning and maintenance of quarries is not helped by the fact that several institutions are charged with its governance. The Ministry of Environment, the Ministry of Interior and Municipalities and the Ministry of Energy and Water have the principal responsibility to regulate quarries, while the latter is required to issue permits when quarries can impact water sources. Often, the Ministry of Interior and Municipalities would issue permits to quarries without coordination with the Ministry of Environment. Continuous war and destruction driving the demand for construction material have complicated the situation further and contributed to the unchecked proliferation of quarries. While existing regulations allows exploitation of the eastern Lebanese mountains, known as the Anti-Lebanon Mountain Range, the western mountains, which provide the main water reservoirs, are illegally exploited to extract sand. Furthermore, demand for rock is expected to further shoot up with the end of Syrian war and cement factories are already bracing themselves for this eventuality. A recent study counted 1,278 quarries spotting the Lebanese landscape that produce aggregates, rock and sand.11 In 2002, a decree established the National Council for Quarries, composed of nine institutions and chaired by the Ministry of Environment. The decree presented a long-awaited National Master Plan for Quarries, which designated the anti-Lebanon Mountain range as a quarrying site. It also requires quarry contractors to rehabilitate the site at the owner’s expense by terracing and planting after completion of extraction and imposes fines in cases of non-compliance. Unfortunately, enforcement of these regulations remains lacking and usually very little rehabilitation of quarries ensues. Hundreds orphaned and abandoned quarries are scarring the face of this small Mediterranean country. The impacts of quarries have gone beyond the visual effect. They have removed topsoil, destroyed valuable vegetation cover, altered ecosystems, caused air and water pollution, endangered water sources and drove down real estate value. While StREG is unable to tackle the country’s political entanglements, it worked closely on providing best practice guidelines to tackle shortcomings and legal strengthening.

StREG experts compared practices in Lebanon with those implemented internationally. This exercise reconfirmed the gaps in controlling erosion, optimizing extraction (more outputs, less impacts), managing dust, minimizing explosives in the blasting process, protecting water sources, and managing emerging waste. The analysis provided authorities with a clearer view of the deficiencies in the quarries system (refer to List of STREG Publications). StREG also revised a draft Quarry Framework Law, which was prepared by MoE in 2006. When passed by parliament, the law will put forth a comprehensive and integrated system for quarries management in Lebanon. The Ministry staff view this as a crucial step that will significantly strengthen their enforcement capacity vis-à- visthe quarry sector.

In favour of the provisions of the law, StREG recommended Best Practice Guidelines to ensure the sound management of the quarries sector in Lebanon. These guidelines should be issued by the National Council for Quarries. The guidelines tackle planning, ways to deal with local communities surrounding the quarries, safety and security, the impact on land, water and air, noise and vibration, transport and how to rehabilitate the plant. Fostering the responsibility of the investor, the guidelines require a feasibility plan covering a description of the project, market conditions, operation, regulatory requirement, mitigation measures, site development, operation and reclamation. Importantly and forward thinking, the investor should also identify impacts on the local community and establish good relations with them. To emphasise protection of natural resources, the guidelines stress the need for proper drainage with a focus on maintaining natural springs as sensitive and valuable ecosystems.